Investigation & Research = Youth analyze and evaluate information in order to learn about and investigate pressing civic and political issues.

In the past, information regarding civic and political issues was identified, assessed, synthesized, and circulated for public consumption by institutional gatekeepers, experts, and elites, such as scholars, journalists, the government, and interest group spokespeople based within formal organizations. Many organizations continue this tradition; however, the changing dynamics of the digital age have lead to expanded opportunities for more participatory forms of investigation. Individuals and groups now have greater ability to check the accuracy of information that is circulated (see reference 1), as well as conduct their own investigations in an effort to actively create knowledge and raise awareness. New media tools such as Internet search engines, survey tools, online databases, mapping tools, and mobile phones with recorders and video cameras all make investigation easier.

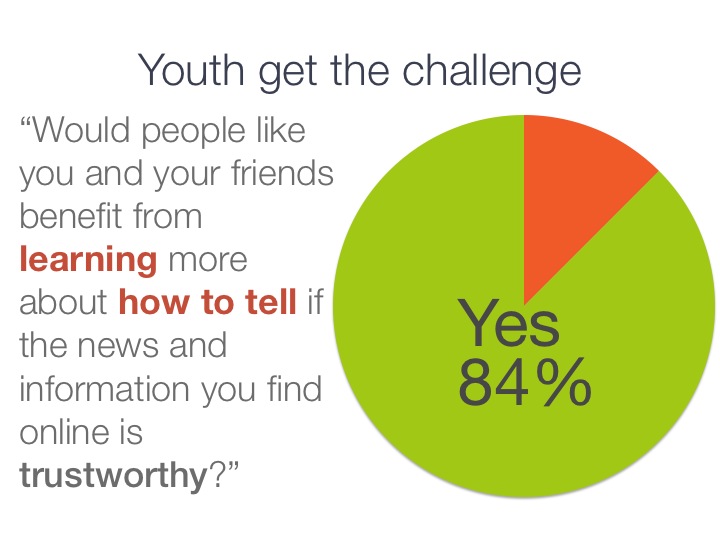

In short, digital networks and platforms enable any individual or group to post and share information without institutional oversight,  however, this has made it more difficult to determine the credibility of the immense amount of information accessible online (see 2). Youth get the challenge. In the 2011 YPP Survey, 84% of youth surveyed nationally said they thought that they and their friends would benefit from instruction in how to tell if a given source of online news was trustworthy. Unfortunately, thirty-three percent of youth in high school in the 2013 YPP survey did not report a single class session that focused on how to tell if information found online was trustworthy. Only 16% reported having more than a few class sessions focused on this topic.

however, this has made it more difficult to determine the credibility of the immense amount of information accessible online (see 2). Youth get the challenge. In the 2011 YPP Survey, 84% of youth surveyed nationally said they thought that they and their friends would benefit from instruction in how to tell if a given source of online news was trustworthy. Unfortunately, thirty-three percent of youth in high school in the 2013 YPP survey did not report a single class session that focused on how to tell if information found online was trustworthy. Only 16% reported having more than a few class sessions focused on this topic.

EPP Resources with an Investigation & Research Focus

-

Participate Module from the Digital Civics Toolkit for Educators

-

Investigate Module from the Digital Civics Toolkit for Educators

-

Investigation & Research collection from the Teaching Channel’s Educating for Democracy Deep Dive

-

Research & Blogging Lesson, 11th grade, by Lisa Rothbard (EDDA)

- Related Blog Post

- Related Blog Post

-

Online Research is a Human Right by Marguerite Sheffer (EDDA)

- Albert’s Lesson Plan: Social Justice through Parody (MAPP)

-

Selected Lesson: 1b – The Internet, Social Media, and the Past (GP/FHAO)

For an expanded discussion of this and other EPP practices see:

-

Redesigning Civic Education for the Digital Age: Participatory Politics and the Pursuit of Democratic Engagement by Joseph Kahne, Erica Hodgin & Elyse Eidman-Aadahl

Investigation & Research

| Common Historical Practices | Expanded Practices in the Digital Age | New Opportunities for Youth | Potential Risks | Implications for Educators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Broadcast media and newspapers were the main outlets for news on civic and political issues.

|

The Internet makes access to a wide range of information easier. |

Youth can easily tap a wider range of information, forms of data, and viewpoints. |

There is increased access to misinformation and information that is not sufficiently vetted. |

Support youth to engage in: Effective search and credibility analysis |

|

Research happened through trusted sources such as encyclopedias. |

News and information is accessible through participatory channels, such as Facebook and Twitter. |

Research can be undertaken and shared independent of institutions and gatekeepers.

|

Filter bubbles and echo chambers result in greater exposure to like-minded people and information and less exposure to divergent perspectives (see 3). |

High quality investigation through multiple sources using digital tools and platforms |

|

Information was highly vetted by elites, gatekeepers, and major institutions. |

Crowd-sourced information can be shared and co-created through platforms like Wikipedia. |

|

|

Tapping social networks to forage for information |

|

|

|

|

Participatory action research

Information framing and story creation. |

For a Printer Friendly version of the above chart, click here: Redesigning Civic Education for the Digital Age - Charts

References

1. Armstrong, J., & Zuniga, M. M. (2006). Crashing the gates: Netroots, grassroots and the rise of people-powered politics. New York, NY: Chelsea Green.

2. Metzger, M. J. (2007). Making sense of credibility on the web: Models for evaluating online information and recommendations for future research. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(13), 2078-2091.

3. Pariser, E. (2012). The filter bubble: How the new personalized web is changing what we read and how we think, Reprint edition. New York, NY: Penguin Books; Sunstein, C. R. (2007). Republic.com 2.0. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University.